In order to create policy people are willing and able to follow, it is essential to understand our constituents’ cultural values and individual behaviours. This gives us a better understanding of the context in which our policies will operate, and how well they reflect what really matters to our constituents.

Why does policy often fall short?

The success or failure of policies can often be due to a mismatch with the culture and lifestyles of the people they are designed to impact. Understanding the values of your audience, clients or constituents is a crucial part of deciding what kinds of policies or nudges to implement. It also requires anticipating the impact of any new policy on gender equality.

In the last decade, the Italian government has been actively addressing the rising need for ageing care. However, their solution were broadly situated in a traditional cultural model in which family is considered the best primary source of care, and women are the main caregivers in most families. However, with more Italian women pursuing education and participating in the workforce, public policies needed to respond to meet the growing care needs of a rapidly ageing population. The government created policies such as a “cash for care” benefit, to help people to hire a family assistant, negotiated collective agreements for domestic workers, and reserved quotas for migrant domestic work. The result has been an estimated four-fold increase in registered female domestic workers in Italy between 1994 and 2011. The policy allowed professional women to remain in the workforce, but failed to accomplish any mindset shift toward assumed gender roles in the home. In other words, caregiving remains women’s work, although now it includes migrant women rather than only wives or daughters.

Instead of addressing the lack of available caregivers by challenging values around who should be the family caregiver or changing the way aged care is provided in Italy at a public service level, the new policies reinforced the idea of caregiving as women’s work. This mindset – where women’s time is demanded for work, child care, aged care and domestic duties – continues to be a barrier to achieving gender-sensitive workplace and welfare policies.

This example shows us the importance of designing solutions by looking at the broader social impacts of their implementation, including giving specific consideration to whether it will help to promote decent work for both genders. Behavioural insights can help highlight our cultural biases.

In addition, it is important to not only have the right intentions or follow an approach that has worked elsewhere, but also to understand the core values and behaviours of our particular constituents. And once we understand the values or biases that can create barriers, we can design programs, policies or even nudges to help overcome them.

“Policy” is a Platonic conception perceived to exist on a higher plane where users are always rational, processes run smoothly and every day is a sunny one. By the time we descend to the grubby depths of “implementation” it’s already too late. Matt Edgar, consultant in service design, innovation and product management.

| Classical policy approach | Behavioural policy approach |

| Led by quantitative insights | Led by qualitative insights |

| Assumes rationality & equality | Recognizes bias & environmental influence |

| Prioritizes economic motivations | Prioritizes emotional motivations |

| Uses market analysis & segmentation | Uses behavioural analysis & persona modeling |

| Based on theory | Based on evidence |

| Relies on measurement & evaluation | Relies on observation & experimentation |

| Mainstream economics | Behavioural economics |

The following video from the New South Wales Behavioural Insights Unit in Australia does a great job connecting the importance of contextual understanding and behavioural insights to creating successful policy.

How do we uncover these important behavioural insights?

To get to these behavioural insights about people, we need to look not just at quantitative data (i.e how many people do or think something) but also at the qualitative data (i.e why they do it, and what their underlying drivers, thoughts and motivations are). When we have an understanding of the WHY before designing policy, we can design it to more effectively reflect people’s behaviours and truly work to support constituents and achieve gender equality.

Techniques to learn from our constituents

There are numerous interview techniques to keep in mind when speaking with our constituents so we walk away understanding what they want, need, and already have covered, and most importantly, why.

- Listen more, talk less. As interviewers, we should listen and ask questions to learn more from our constituents. Avoid influencing the conversation by stating our own opinions.

- Keep the questions open-ended. We should avoid questions that can be answered with yes or no, or directional questions that steer answers in a certain direction. Open ended questions (why and how) help us gain more and better information, and give us an opportunity to ask more.

- Ask WHY. Following up (“probing”) multiple times into WHY the interviewee thinks or feels in a certain way helps us get a deeper understanding of their motivations and cultural context.

- Go with the flow. An interviewee might introduce unplanned topics, and one of them might be the key to a value we hadn’t considered, so we should be flexible to changing the subject (while keeping track of the overall objectives). An open mind is key to greater understanding.

- Get reactions to ‘cultural artifacts.’ We can learn a lot about important cultural values by showing interviewees a physical object, scenario, or image, then probing into their reactions and reading between the lines of their responses.

How to use what we’ve learned

As we have learned, ingrained culture can be highly influential in determining the effectiveness of a policy or program. When policy pinpoints the real behaviours and biases of constituents, it can nudge people toward behaviour change with little or no resistance, generating powerful subconscious cultural shifts.

In a behavioural policy approach, we translate insights into an understanding of the system, where behavioural science tools can intervene naturally and effectively. Applying these insights to the policy cycle is complicated and takes time; experts rely on a balance between divergent and convergent ways of thinking, participant observation and critical analysis. The following steps give a high level introduction to the process.

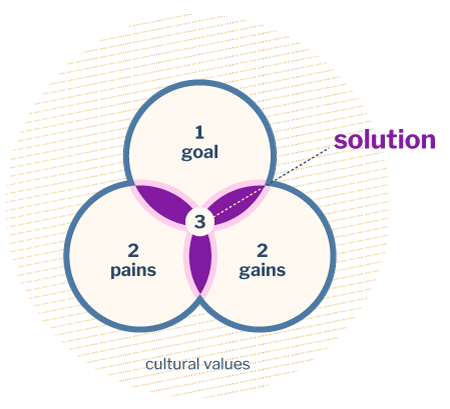

- Identify the problem: Start by understanding what issue we need to solve, and our constituents’ core goals and the cultural values in their environment.

- Identify pains: Look at the behavioural insights we have uncovered that reveal pain points constituents are currently experiencing. “Pains” are things that annoy or hold our constituents back from achieving their goals (or accomplishing their jobs).

- Identify gains: Look at behavioural insights we have uncovered that reveal benefits for our constituents. “Gains” illustrate their desires, or things they will gain and appreciate when our policy or program succeeds. These can be functional utility, social gains, or cost savings.

- Design a solution (outcome): Finally look at all of these elements together to determine where there are shared territories we can address with policy. Keep local cultural values in mind, such as values around gender, family, age, education, or ethnicity. These are often very strong and impact decisions in other functional areas of life. The appropriate human-centered solution may be a nudge, but it may also be any number of other influential behavioural science tools.